Updated December 4, 2025 6:52 AM PST

The Ghost Gang That Built White Los Angeles — And Then Erased Itself From the Story

Spook Hunters Gang

Years Active 1930s-1960s

Criminal Activity

vandalism

fire bombings

assaults

hate crimes

battery

Allies

Other White Racist gangs

Rivals

African Americans & Mexican Americans

Territory

South Gate, Compton, Huntington Park, Watts, Downey, Lynwood, and Inglewood.

THE SPOOK HUNTERS: THE GHOST GANG THAT BUILT WHITE LOS ANGELES

There’s a story white Los Angeles tells about itself. It’s the one where the suburbs were peaceful, the streets were safe, and the neighborhood was “nice” back when people “knew how to behave.” It’s a myth preserved in real-estate listings and Facebook nostalgia groups , and it collapses the moment you mention the Spook Hunters.

In the 1940s and 50s, long before “white flight” became an official demographic trend, the Spook Hunters patrolled places like South Gate, Huntington Park, Lynwood, and Compton, not as a “street gang” in the modern sense, but as a racist youth militia. Their mission was simple: keep Black people out through intimidation, assault, and terror. These weren’t rebels. They were the unofficial foot soldiers of segregation, policing racial boundaries that banks and zoning commissions had already drawn on paper.

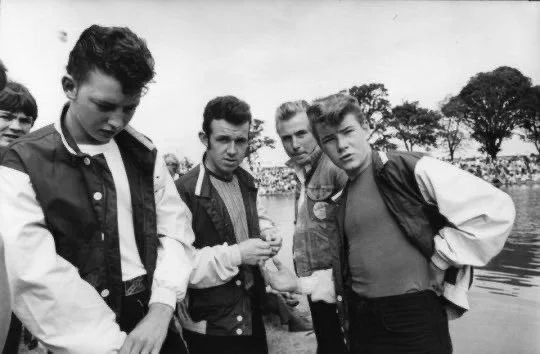

They wore varsity jackets. They carried pipes and chains. They hunted, literally, for Black families who dared walk into neighborhoods federal housing policy had already redlined. They chased kids from pools. They ambushed teenagers walking home. They enforced sundown-town rules in cities that pretended they never had them.

And here’s what polite Los Angeles never says out loud, White gangs existed first. Not Black gangs. Not Mexican-American gangs. White gangs, violent, organized, and ideologically driven. The Spook Hunters were not an anomaly. They were a blueprint.

People Think this is in the past and it doesn’t matter anymore. It isn’t and it does matter. When people talk about Compton becoming “Black” in the 1960s and “Latino” later, they skip the part where white mobs enforced invisible borders with violence before any demographic shift. LA County’s segregation wasn’t just written into covenants, it was enforced with fists. It was teenagers doing the dirty work of racial maintenance.

They saw themselves as guardians. Guardians of whiteness, property, and the mythology of “good neighborhoods.” They grew up, bought homes, joined unions, ran for office, and built wealth.

And the families they terrorized were pushed into underfunded, excluded cities. That gap is structural inheritance, not coincidence.

It was this violence, white teenagers patrolling neighborhoods and attacking Black and Mexican American youth, that pushed those communities to form their own groups for protection. The earliest Black and Latino street organizations weren’t born from chaos, they were born from survival.

Spoke Hunters Gang

The Afterlife of a Gang Has No Archive — Only Evidence

There’s no museum dedicated to the Spook Hunters. No Hollywood documentary. No true-crime series. But their imprint is everywhere. Cities like South Gate and Huntington Park are now over 90% Latino and nearly 0% Black, the demographic scar of mid-century racial violence. Residents still say “that area changed” like it’s a crime scene, never mentioning who created that “change.” City councils across the county still weaponize “property values” as coded language for who belongs. Neighborhoods built on segregation now disguise it as “local character” and “preserving community.”

But Drive east, to Pomona. Not because the Spook Hunters operated there, they didn’t, but because the ideology migrated. White fear didn’t disappear when neighborhoods integrated. It moved. It rebranded. White flight wasn’t an escape. It was a strategy, a redistribution of whiteness across Los Angeles County. Pomona absorbed the aftershock. Panic over apartments, nostalgia policing, and the quiet assumption that safety is a racial commodity.

Everyone in Southern California understands the stereotype, gang violence is Latino. Or Black. Reporters treat it like weather, predictable, racialized, inevitable. But where are the white gangs? Where are the documentaries? Where are the police panels? Where’s the moral panic? They existed.

They were documented. They shaped entire cities.

And yet, white gangs were never branded as public-safety threats. They were “rowdy boys,” “kids protecting their neighborhoods,” “teenage antics.” Their violence was allowed to age into respectability.

The Spook Hunters got memory-holed into polite euphemisms like:

“changing demographics”

“the neighborhood went downhill”

“we moved for the kids”

And the white gangs in and around Pomona, the ones who fought Mexican-American youth in the 1950s–70ss, vanished entirely from the official record. It wasn’t simply forgotten. It was left out. Because acknowledging white gangs requires saying the part LA has spent 70 years avoiding.

California Eagle News Paper

Los Angeles, California • Thu, Apr 7, 1960Page 4

California Eagle News Paper

Los Angeles, California • Thu, Apr 7, 1960Page 4

The California Eagle documented Spook Hunter violence in real time, Black teenagers beaten, chased, and ambushed when they crossed into “white” areas, while police openly ignored the gang’s attacks. One Eagle report noted that officers stopped Black kids “to tell them to go back to their side of town,” yet “the Spook-Hunters come into Negro territory and are not molested by police.” Meanwhile, white officials publicly insisted the gang was “only rumor,” claiming they could find “no evidence” despite widespread community testimony. It was the perfect blueprint for how white violence gets erased: the attacks were real, the victims were real, but the archive was sanitized. The denial wasn’t ignorance, it was strategy.

White people didn’t flee the gangs, they were the gangs. And they got to grow up, buy property, and write the history.

The Erased White Gangs of Pomona

Pomona’s gang history gets told like only Latino or Black neighborhoods ever existed. The lists are always the same. Lavarne, 12th Street, Cherryville, HTR, Sin Town, and Ghost Town, the usual shorthand. But older Mexican American families remember something else. White kids patrolling streets. White male youth starting fights. Groups of white youth that looked, acted, and operated like gangs, even if the city refused to call them that.

There are scattered oral histories describing white youth groups in mid century Pomona, informal collection, most likely with comb-overs hair cuts who clashed with Mexican-American teens long before the city’s modern gang narratives took shape. These groups never received names in police reports, never appeared in gang injunctions, and were eventually folded into suburbia as the city changed. Hollywood even captured this kind of racial conflict in Gang Boy (1954), a film centered on a white gang and a Chicano gang, a reflection of the era’s tensions that Pomona and many nearby cities quietly absorbed but never officially documented.

White violence gets written out. Latino violence gets written in. And that editorial choice becomes public memory. Here’s where the relevance snaps into focus. The Spook Hunters didn’t create modern white nationalism. But they were an early, local expression of the same instinct, protect whiteness through space, fear, and force.

The names change, segregationist mobs, neighborhood-defense gangs, suburban anti-housing groups, the alt-right, but the impulse remains, claim the street, define who belongs, punish intrusion.

Today the weapons look different. It’s HOAs policing renters, anti-housing coalitions defending “neighborhood character”, Nextdoor app panics about “suspicious Black or Brown teens” Facebook patriot groups rehearsing vigilante fantasies, and Zoning meetings that sound like coded segregation meeting.

The Spook Hunters didn’t disappear. They were promoted. Their grandchildren aren’t carrying chains, they’re carrying out voting blocs, school-board takeovers, and anti-housing crusades. The violence evolved. The logic didn’t.

The Generational Lineage: From Silent Generation Fists to Boomer Policy

The Spook Hunters weren’t Baby Boomers, they were their parents. Most Spook Hunters were teenagers in the late 1940s and early 1950s, part of the Silent Generation, the friends and their ally’s that enforced segregation with fists while the country pretended to be “postwar and peaceful.” They patrolled streets, defended racial lines, and punished intrusion. Then they grew up, bought homes, and entered civic life just as their children, the Baby Boomers, were coming of age.

And this is where the violence shapeshifts. The Silent Generation used pipes and chains.

The Boomers used zoning meetings, PTA boards, and real estate law. The children of the Spook Hunters didn’t need to swing anything. They inherited safe neighborhoods, rising property values, and the political language to keep it all intact. “Good schools,” “quiet streets,” “neighborhood character,” “property values,” “keeping things the way they used to be”. They were the polite vocabulary of the same racial boundaries their parents enforced with brute force.

One generation patrolled the block. The next one codified the block into law. The ideology never died.

It just got a mortgage and grandchildren.

People imagine white nationalism as a Southern export with hoods, crosses, Confederate ghosts drifting through the smog and bad air the further you go inland. But lets not forget California has its own lineage, a state shaped by pro-Confederate settlers, suburban borders that appear polite, but come with a territorial instinct that is on full blatant display on the Nextdoor apps and community Facebook groups across America.

The South had the Klan. Los Angeles had white teenagers in letterman jackets swinging pipes at Black kids walking home from school. The most dangerous thing about the Spook Hunters is not that they existed.

It’s that they were never interrogated.

Their violence was absorbed as, neighborhood pride, “good schools, and safe communities. I would call this segregation with manners.

The Past Isn’t Past — It’s Policy

When people say “those days are over,” remind them, zoning still enforces racial boundaries

HOAs still police who belongs, neighborhoods still weaponize, “safety”, and housing policy still protects whiteness.

The Spook Hunters never needed to join the Proud Boys. They didn’t need tiki torches or swastikas. They won when the system adopted their logic.

The ghost of the gang is still here. Some of them show up in the comments, tossing out racist tropes on Nextdoor. Others sit on city councils and state senates, some serve as commissioners, and plenty call themselves Democrats or Republicans depending on what helps their political agenda.

Unless people name it, plainly, we’ll keep pretending the only gangs that shaped Los Angeles were the ones easy to criminalize. The truth is simpler and uglier. One gang grew up and inherited the city. And we’re still living inside its territory and their reality.

History doesn’t disappear. It just waits for someone to name it again.

LAist — Mentions Spook Hunters as the first major white gang terrorizing Black and Latino families.

Saving Places — Documents white youth patrols and Spook Hunter activity in Compton and South Gate.

California Eagle (1950s) — Black newspaper reporting assaults, intimidation, and white mobs.

LA Civil + Human Rights Dept. — Notes white youth gangs predating Black gangs.

StreetGangs.com — Frames Spook Hunters as the racist predecessor to modern Black gangs.

Cornerstone Journal (UCR) — Academic documentation of white youth gang violence.

Gang Boy (1954) — Rare depiction of white vs. Chicano gang rivalry.

TIMELINE

1930s–1940s — White-only covenants dominate LA.

1940–1955 — Spook Hunters patrol South Gate, Lynwood, Huntington Park, Compton.

1954 — Gang Boy (white vs. Chicano gangs) released.

1960s — White flight expands east into Whittier, Claremont, Pomona, Covina.

1970–2000 — White gangs disappear from public memory; Latino/Black gangs dominate headlines.

2010s–2020s — The ideology resurfaces as alt-right suburbia, anti-housing politics, and racialized “neighborhood watch” culture.

SOURCE NOTES

California Eagle archives

LAist, “How Compton Became the Violent City of Straight Outta Compton”

National Trust for Historic Preservation, “Recognizing Compton’s Historic Legacy”

LA Civil Rights Dept., “African American Experiences in Los Angeles”

StreetGangs.com (Alex Alonso)

Cornerstone Journal, UCR

Gang Boy (1954)

Julian Lucas is a darkroom photographer, writer, and a bookseller, though photography remains his primary language. He is the founder of Mirrored Society Book Shop, publisher of The Pomonan, and creator of Book-Store and PPABF. And yes he will charge you 2.5 Million for event photography.