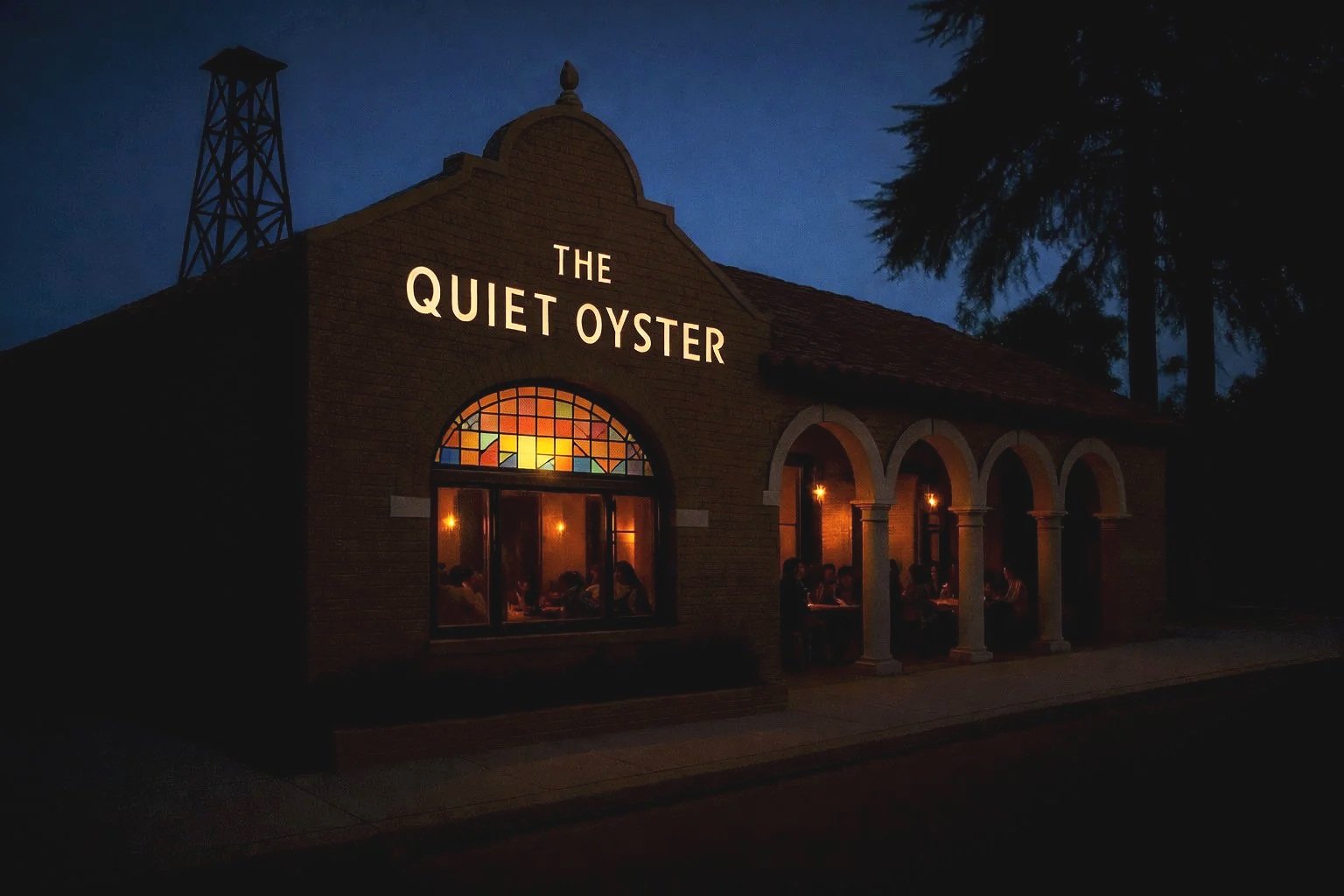

Illustration Julian Lucas ©2025

We were sitting at the furthest table at The Quiet Oyster, oysters on ice between us, the room doing that quiet, self-possessed thing it does when it’s full. A martini crowned with olives individually hand-stuffed with blue cheese and anchovy. A Negroni stirred deliberately with gin, Campari, and sweet vermouth, finished with an orange peel expressed just enough to wake up the bitterness.

Then the bottle of New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc. Sharp, clean, and praised for its green, flinty notes and depth. Textured and uncomplicated. I poured without asking. That mattered.

We ordered a dozen oysters. Bub’s & Grandma’s bread, butter. She reached for the lemon. I didn’t. This has

become a known difference.

It was the second restaurant I’d opened, housed in a fire station that had been vacant since the 1990s. Decades of quiet had settled into the walls, and the room carried that patience easily.

She lifted an oyster, looked at it for a second, then said it plainly, without warming up the sentence.

“You like to paint with a broad brush. You can’t make a blanket statement like suburban art is different from art in metropolitan areas.” A continued conversation from the car.

There it was. I smiled, mostly because she was right and we both knew it. “I do,” I said. “I just shouldn’t.” She smiled softly with slight funny irritating smirk and took a sip of her wine. “That’s lazy,” she said. “You like to put people in categories.” I swallowed an oyster, brinier than hers. “I’m talking about risk,” I said. “About what’s allowed to happen.” She shook her head, not dismissively, just patiently. “Art is art,” she said. “And half the stuff you’re talking about isn’t even that different.” We let that sit while the bread disappeared. But I ordered more bread. Because Bub’s and Grandma’s bread is the answer.

I brought up a gallery we frequent sometimes. It always comes up. She didn’t hesitate. “Ehh,” she said. “It reminds me of art in Pomona.” My eyes opened wide, like deer in headlights, totally in disbelief. “And all the nude women in the photos is “snore bore.” That one landed because I agreed. “It does become redundant. Although very different, the idea, pretending it’s transgressive.” “And honestly,” she said, “a lot of the work looks the same at that gallery.”

But lets remember, the body is one of the oldest tools in art. The question isn’t whether it’s there, it’s why it’s there. The same body once filled churches without apology, long before galleries learned to flinch. I mentioned the Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo’s frescoes are filled with nude figures, prophets, angels, bodies.

But she wasn’t wrong. Most of it blurred together, point and shoot cameras, Kodak Gold, irony worn thin from overuse. Different artists, same visual sentence. Over and over again. But every generation of photographers has its thing.

There are exceptions,” I said. “Some photographers make photos that’s distinct. There’s history. Weight. Intention.” And to be fair, that particular gallery exhibits work that pushes beyond boundaries.

She gravitates toward the masters. Chuck Close especially—the discipline, the patience, the way the work earns its gravity over time. I love that too. I just tend to lean further forward, toward contemporary work, sometimes lowbrow, where things are still unsettled.

She agreed, but carefully, like she didn’t want that to become a loophole.

We ordered scallop tostadas next. Crisp, delicate, just enough heat to keep the conversation awake. Another bottle of white followed, colder than the first. The Trout collar followed by the Cod Sandwich.

“And yet,” I said, “I still appreciate what that gallery does.

She looked at me, waiting.

“They don’t hold back,” I said. “They let the work exist without apologizing for it. They don’t pre edit for comfort. That’s where I always get stuck.

It’s not that every gallery needs to shock. It’s not that everything needs to be out there. It’s that so many spaces, especially the smaller cities east of LA spaces start negotiating with the audience before the art even arrives. Anything that pushes the envelope gets hidden, even when it’s thoughtful. Risk gets diluted. Work that might breathe gets quietly smothered in advance. And for what it’s worth it’s not for shock value. It’s the reality of the artist and its culture. Out here in the burbs, galleries perpetuate the culture war by playing it safe, mistaking restraint for responsibility.

“I’m not saying all art should be the same,” I said. “I’m saying let it live. Let it irritate someone. Let it make someone uncomfortable. Let someone love it and someone else get angry. Art is supposed to make you feel something. It doesn’t all have to behave like a Hallmark card.

She took a sip of her wine.

“That’s art doing its job,” I added. “Not being agreed upon.”

She didn’t argue with that.

I brought up other galleries we spend time at on the west side. Imagine if they hid the work in a back office, tucked away where no one could see it. They’d be out of business within a year. So how do these art spaces expect to survive? Is it all just for show, or are they actually invested in the artists they claim to support?

I said what I’m usually not supposed to say out loud. A lot of these places aren’t really galleries at all. They’re frame shops with gallery space attached. That changes everything. When your business is selling frames, the art becomes an accessory, not the point. Photography “doesn’t sell” because it isn’t being treated like work that deserves to be sold. It’s being filtered through caution, through wall color, through what won’t upset the regulars. If photography truly didn’t sell, there wouldn’t be entire galleries on the west side of Los Angeles devoted to it. They wouldn’t survive. The difference isn’t the medium. It’s the willingness to stand behind it.

I asked her what artists had really emerged from the burbs lately. Not Instagram famous for a weekend, but artists with legs. There’s a massive opportunity out here to stop slapping a parental advisory label on everything, to stop sanding down the edges, and instead actually produce artists. Not safe work. Not polite work. Real work.

We ordered a half dozen more oysters because at some point the debate mattered less than staying. The conversation softened, looped back, drifted again. Artists we loved. Work we didn’t trust. Art that felt alive. Art that felt polite.

She glanced around the room, then back at me.

“This place,” she said. “You built it quiet on purpose.”

I nodded.

“See?” she said. “Not every restaurant has to be a club with music so loud you can’t have a conversation with the person in front of you. The 1990s was 35 years ago.

I smiled because she was right again.

“I paint with a broad brush when I get lazy,” I said. “When I slow down, I can see the difference too.”

She reached for her glass. We didn’t settle anything. We never do. And thats what’s beautiful.

Some conversations don’t need conclusions.

They just need oysters, good bread, a perfect bottle of wine, and enough trust to keep disagreeing without trying to win.

Julian Lucas is a darkroom photographer, writer, and a bookseller, though photography remains his primary language. He is the founder of Mirrored Society Book Shop, publisher of The Pomonan, and creator of Book-Store and PPABF. And yes he will charge you 2.5 Million for event photography.