Published April 1, 2024 | 9:50am PT

Updated 5/9/2024 | 1:37pm PT

Pomona is a city of endless possibilities, but its vices overshadow it. It lies underneath its own dark cloud. However, even its biggest detractors can sense the fragrance of a mosaic city that-never-quite-became-a-metropolis. The striking red pomegranate trees fill the front yards. Limes and oranges grow in the backyards while cactus stand at attention as they climbs over chain link fences.

At this point, Pomona is past its prime - or between its prime - and has all the vestiges - or the promises - of what once was, or could be, a flourishing city.

Even so, when Pomona flourished in the past, it was never for everyone. Now is the time to rebuild a different Pomona with a different vision.

When a city like Pomona has an abundance of resources, what does the vision for the future look like? Can Pomona be the next mecca of culinary culture? Can Pomona’s farms and street vendors, restaurants collaborate? Or will we continue down the path of separatism, individualism, racism, nepotism, classism, cronyism, and political warring?

Street vendors who serve food are an important aspect of Pomona’s past, present and future. It is over food that people come together. Conversations revolve such things as - ‘the chile is hot as fuck!’ or ‘This is my favorite (mi favorita) spot!’ Everyone can join in, food is a unifier.

The food prepared and served on the streets fuels the city, and the street corner is a place where anyone can go and be immersed in the energy of the culture. On any given night, street vendors bring in a crowd of over 300 people drawing people from the surrounding cities and beyond.

Growing up in the 1980s as a youngster, I came to Los Angeles from the midwest, and I remember how the lunch trucks would line up from their gated lot. Some people called them “roach coaches,’ but I didn’t like that because I felt like they were the coolest thing and that it was such a treat to eat from a truck that sold food.

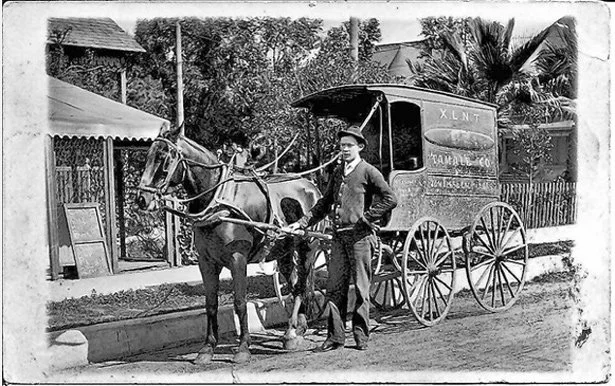

Photo of Nicholas Martinez

The first documented street vendor

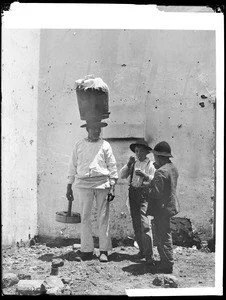

Los Angeles has a long history of street vending. Going back to the 1860s, the first street vendor in Los Angeles was Nicolas Martinez who carried a basket on his head which was split down the middle with wood - one side was tamales and the other side was ice cream. He kept them warm or cool with towels he used to insulate each side. Selling his food in the area around 7th and Spring to Sonoratown, tamales cost 5 cents and ice cream 10 cents. In his arms, Martinez carried water to clean the silverware and glass dishes.

However, by the 1890s, Martinez faced opposition. In 1892, L.A. officials tried to ban street vending, and, in 1897, L.A. City Council, in response to a letter signed by restaurant owners, proposed not to allow tamaleros to operate before 9pm. However, that didn’t work, and the city realized they had more to gain by extracting revenue from them rather than banning them. By 1901, more than 100 licensed tamale wagons roamed Los Angeles paying one dollar a month for their city business license.

It wasn’t just Latinos who operated the tamale wagons - African-Americans, European immigrants and whites also joined in. In 1905, even the YMCA opened a temporary tamale wagon in order to raise funds so it could send a boy’s track and field team to compete in Portland, Oregon. (ARELLANO, GUSTAVO. Tamales, L.A.’s original street food: LA Times 9/8/201)

These wagons sold everything from oyster cocktails to sandwiches, popcorn to pigs' feet, but most sold tamales cooked elsewhere and kept warm in steam buckets.

The City of Los Angeles again tried to ban street vending, but Council Member Fred Wheeler defended them, stating, “The tamale put Los Angeles on the map, these wagons are an institution of our city, drive these wagons from our streets, never!”

Currently there are over 50,000 street vendors in Los Angeles, 10k of which sell food. It is estimated to be a 500 million dollar industry, creating over 5000 jobs.

In a 2018 Curbed article it was reported, in 2012, the late famed food critic Jonathan Gold was asked to be a part of Los Angeles Food Policy Council. Jonathan insisted on including street vendors as a critical part of LA’s food system. At that time members of the council formed the LA Street Vendor Coalition the same year, with a goal to propose an ordinance to legalize street vending. Rudy Espinoza, the executive director of Leadership for Urban Renewal Network who is part of the coalition, remembers Jonathan tearing up after hearing a presentation to the task force about how vendors were being targeted by law enforcement.” “When he heard that some of the entrepreneurs he frequented were being criminalized, he was visibly emotional and in shock that the city would target these entrepreneurs,” Rudy remembers. “He recognized that the best food was often found in low-income neighborhoods and was made by street vendors.”

In February of this year, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors unanimously 15-0 approved two ordinances governing sidewalk food vendors. The board also approved a program to help cover the permit expenses associated with the new regulations.

Supervisor Hilda Solis estimates that there are roughly 10,000 sidewalk vendors selling food in the county - most of them coming from Latino or other communities of color. Solis, in her statement after Tuesday’s final vote, emphasized that it is important to both foster and celebrate these micro-entrepreneurial efforts, reminding everyone that if the county’s financial barriers are too high it will cause the system to collapse:

"Sidewalk vending, including food vending, represents an integral part of the cultural and civic fabric of Los Angeles County, This is especially true in the First District, where communities like East Los Angeles have long been a hub for food vending. For many residents, especially those from low-income or immigrant communities, food vending represents one of the few economic pathways to attain financial independence and stability."

“With this ordinance, for the first time in recent memory, L.A. County sidewalk vendors now have a legal path to build their business and help grow our regional economy,” “As we celebrate this milestone, we’re grateful to the Board and the Department of Economic Opportunity for their ongoing commitment to a comprehensive set of programs to remove barriers, reduce costs, and promote greater economic inclusion.”

The same day, the Los Angeles City Council voted to give vendors in the city significant relief from what would have been a $541 annual fee for permits to conduct business, and approved lowering their cost.

The new law supports individuals in legally operating a sidewalk vending business on sidewalks and pedestrian pathways in the unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County. The Board’s action codifies the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act (Senate Bill 946), passed in 2019 to decriminalize sidewalk vending in the State of California and to allow local authorities to develop guidelines and infrastructure to formalize the sidewalk vending industry. The County law specifically creates a Sidewalk Vending Program run by the LA County Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO), a Sidewalk Vending Registration Certificate and annual fee for all mobile and stationary vendors, clear operating rules and regulations related to distancing, hours, and waste disposal, and fines and other penalties for non-compliance. The law will go into effect in August 2024. LA County

The first ordinance that the board approved specifies the conditions that must be met in order for "compact mobile food operations," or smaller businesses that operate using carts or other non-motorized equipment, to obtain a health permit. All vendors inside the county will be subject to the legislation, with the exception of those in Vernon, Long Beach, and Pasadena, as those cities have their own health departments. Recently, Long Beach's own ordinance on sidewalk selling was enacted.

Under the LA county ordinance, obtaining a health permit will require the vendor to pay an initial fee, ranging from $309 for a low-risk operation selling pre-packaged food to $1,186 for higher-risk vendors who prepare and sell hot food, such as a taco stand or hot dog cart. Vendors will then have to pay ongoing annual fees ranging from $226 to $1,000, depending on the type of vending.

To that end, supervisors approved a related motion from Supervisor Hilda Solis that would make low-income street vendors in unincorporated county areas eligible for a 75% fee subsidy.

A Historical Perspective: Street Vending as an Economic Pathway

Pink’s Hot Dogs

Pink’s started out in 1939 by Paul and Betty Pink, with a pushcart they purchased for $50, with money they borrowed from Betty’s mother. The land on which the pushcart stood was leased by Paul and Betty for $15 per month. They used a long extension cord they plugged into a hardware stores outlet to power the heating mechanism to heat the hot dogs. They sold hot dogs for 10 cents and cokes for a nickel. Pink’s offered curb service, and sold 100 hot dogs a day.

Carl's Jr. (The Blimp)

Carl N. Karcher, started his business with his wife, Margaret, from $15 of his own savings and $311 he borrowed on his car. In 1941, they purchased a hot dog cart (The Blimp) in L.A, and soon grew their small business, eventually expanding the Carl’s Jr. The chain became one of the first in a new breed of restaurants that formed the quick-service restaurant industry.

Don Miguel

In 1906, Alejandro Morales, from Sonora, Mexico, began selling his wife's tamales from a tamale wagon in Anaheim. Morales, who was a ditch-digger by trade, eventually developed the concept into a restaurant, then a factory that made tamales, and ultimately Alex Foods, a multibillion-dollar company that is now known as Don Miguel Mexican Foods.

Guerrilla Tacos

Guerrilla Tacos started its journey as an illegal street corner cart, which evolved into a legit food truck, and then a brick-and-mortar location in the heart of the Arts District in DTLA.

Wes Avila was employed as a sous chef at Le Comptoir, a pop-up eatery. Avila claims he wasn't making enough money to pay his rent because it was only open for business four days a week. So he purchased a basic food cart. His final $167 was spent on ingredients. Subsequently, he and a companion started vending tacos in the downtown Los Angeles artists district, lacking the necessary health department permits. He moved to different locations in a guerilla-warfare manner in order to avoid risking being fined. Availa states in an interview, "That's why we had that name, because we'd be in random alleys, random streets, being kind of renegade like that.”

Photography Julian Lucas Pomona, CA 2018

Being the 7th largest city in southern California as well as the touted “compassionate city”, can Pomona leaders take an initiative and a progressive approach or mirror the model of other cities to create policies that support and offer street vendors a seat at the table? Will Pomona residents support the efforts of its leaders in creating such supportive policies? Can the community come to an understanding that street vending can be the stepping stone to a culinary mecca?

LINKS

LA County

Los Angeles Times

Curbed LA

Julian Lucas, is a photographer, a purveyor of books, and writer, but mostly a photographer. Don’t ever ask him to take photos of events because he will charge you a lot of money. Julian is also the owner and founder of Mirrored Society Book Shop, publisher of The Pomonan, founder of Book-Store, and founder of PPABF.