Text L.V. Loya Soto

My mom has always told me, “por que no eres un nina normal” echoing one of the reoccuring punchlines of La familia P. Luche. Like Bibi P. Luche, I was also la rara, a studious quiet child who was unlike the rest of my family. I was someone who relied on this withdrawn nature to mask the struggle and confusion I felt within. I’ve always felt different. At first, I thought that meant I was wrong.

Femininity, especially femininity from a traditional Mexican perspective, was like a heavy beaded gown, fun for a game of dress up every now and then but not sensible for long-term wear. When I was young, and my parents were still together I was their golden child. A sweet and smiley little girl who adored playing dress up as much as she loved climbing trees. My amá took pride in my appearance, picking out darling frilly outfits for me to wear. She would spend hours on my hair, pulling my thick dark brown mane this way and that. Pigtails and braids and curls and barrettes in every color. Time with my mother was so precious, especially after the birth of my first brother and my parent’s subsequent divorce, when her time became dominated by her 40-hour-a-week warehouse job. Before the divorce, my mother would read to me as I sat in her lap and we rocked back and forth in her big plush rocking chair, her accented English the music of a mother’s love in my ears. After the divorce, the only time she had to spare was used to get me ready for school, waking up extra early to do my hair after she had already gotten ready for work, my baby brother packed away in his baby carrier fast asleep. I cherished this time together even if I had to bite my lip to keep from squealing as she stretched hair across my scalp. La belleza cuesta, she’d say the times I did protest. Beauty costs.

She would be exasperated when I returned home each day, sweat plastering stray hair to my face, my pigtails wilting, my pretty clothes covered in thick sap from scaling the surrounding trees. This was the last time I felt some semblance of agency in my body for quite some time, feet searching for the next secure knot, arms pulling me up higher and higher until I was above my apartment complex, looking out over my corner of the world and wondering where I fit in it. I climbed trees and raced neighborhood boys until my developing body suddenly made it improper for a girl like me to be out in the streets. This was around the time my mother married my stepfather after a brief courtship at work. My stepfather was an alcoholic with enough traditional Mexican machismo to be terribly confused and angry at me for failing to meet his expectations of femininity. Especially when my mom is un mujer propio, never leaving the house without her hair or makeup done. Extremely demure, my amá serves it to them in her signature silver eyeshadow, blue eyeliner and pink blush. No lipstick and neither hemline nor neckline showing more than what was appropriate. My stepfather couldn’t understand how someone like me could come from someone like her. Not only was I indifferent about my appearance and developed an aversion to frilly girly clothes, but I refused to play my part as doting daughter. The worst part was that I was smart, which meant I was willfully disobedient, a cardinal sin as a first born girl child.

ADVERTISEMENT

I kept being struck by how unfair this was—why was my body changing? How could something that once pulled me strong and true to treetops betray me so terribly? At 9, my breasts started budding, and I was already a head taller and several pounds heavier than the rest of my classmates. My body hair turned from golden to dark black and seemed to cover me all over. I had stretch marks across my hips, legs and breasts. I felt like a werewolf mid-transformation. I felt alien and wrong. My children’s clothes did not protect me from the adults who sexualized my body. Men would call out vulgarities from cars, honking their horns as they whistled at me and my light up shoes, my sequined Bobby Jack sweater. At this point I was already a sexual abuse survivor as well, and this new body frightened me to no end. I grew my hair long and wore it down. I lived in oversized sweaters year-round, trying fruitlessly to hide in the fabric. This shame I felt about my developing body extended to shame about my ethnicity as well. Which I also tried to hide.

I developed a healthy amount of internalized racism that manifested in lies to classmates: I was half Italian in grade school, born in Italy in high school. I lied about who I was, where I came from, to try to distance myself from the way I saw my mother treated. I was terrified of ending up like her, a beautiful strong honest woman who was pregnant at a young age and shackled to a full-time warehouse job. I didn’t want to putter around the house, spending all of my free time cleaning up after everyone else. The more I distanced myself from my heritage, the more I assimilated I became the more control I felt over my future. The less Mexican I felt, the less indebted to these sexist traditional ideals I felt. I hated the assumption that I would get married, have children, and serve them all a plate before I sat down. I hated that family would ask me about prospective boyfriends before prospective colleges. I hated being delegated to housework when none of my brothers had to so much as wash a dish. I love my family, and owe my life to them, but the sense of duty that hung over my head was suffocating. Once in high school, I joined marching band, pride club, yearbook—desperate to find obligations and responsibilities at school that could act as fuel on my rocket out of town. The sense of duty I forged, independent of my assigned gender or ethnicity, wholly dependent on my skill and talent, felt earned instead of inherited. It was hard not to feel resentment towards my culture, especially since representation was few and far in-between.

Our Mexican culture exists in liminal spaces—on the car radio, on television, at certain markets or family parties. We have to extend our hands, and ask for bits of Mexican culture, as we seep in American ideals. Although Latinx people were all around me growing up—both in the towns I lived and at school—I never saw them in positions of power. I went to school in Pomona, Ontario, and Chino where all of the teachers I had were white up until college. I didn’t know any whose parents went to college. Parents in our neighborhoods were forklift certified, employed at the various warehouses that continue to pollute communities in the Inland Empire and San Bernardino County. Those of us who expressed interest in higher education were encouraged to seek out practical careers. Many went to vocational schools and became nurses and dental assistants, drawn to a steady paycheck with unwavering demand. Artists, writers, and those of us with stars in our eyes were met with much less support when expressing pursuing things related to the arts. This was seen as a waste of opportunity and potential. My mother hardly spoke of her time in Mexico, but she would often remind us of the struggles she faced to get to school, telling us of the miles she’d trek in the early morning while the sun still slept behind the horizon. Sacrifice, guilt and the shouldering of burdens seemed to be the only constant in our culture, the only things taught.

Although Spanish was my first language, it quickly felt clumsy and heavy on my tongue, worn away by lack of practice or immersion. As my mother’s first born, I have been her translator since grade school, sitting in on phone calls to bill companies, performing alchemy with each whispered word. I’ve witnessed firsthand how quickly patience is lost if you don’t speak the same language. Ditto if your accent is too heavy. I quickly understood that English was prioritized in every conversation, often with little to no Spanish alternative. English became my best subject, a strength hewn by a love of reading born of my mother’s bedtime stories. Meanwhile my Spanish has stuck around conversational grade school level. I can read, if I take my time and sound out each word but can’t write much, at least not confidently. I’m grateful for the scraps I have, since a few of my younger brothers, like many other Latinx first and second generations, can’t speak Spanish at all. Language, like any living thing, must be nurtured and shown love or, like any living thing, it can die. Many families don’t speak Spanish because their grandparents had their knuckles rapped by wooden rulers for every word spoken at school or church. In my neighborhood, foreign languages only mattered on high school transcripts and resumes for part time jobs at the mall. In the real world, no one gives a fuck if you speak Spanish. Value, love and appreciation for our culture must be taught or this world makes us forget, or worse—assimilate.

High school was a major turning point for me. My involvement with marching band and various clubs meant I was on campus often, granting me freedom to find myself. It was my involvement with the pride club in particular that spurred my self-discovery, starting first with the realization that I was not merely an ally, but a member of the community. The more I was able to immerse myself and learn about queer culture, the more confidence I built. Our advisor was wonderful, taking the time to not only teach us about the various categories and labels in the queer community, but queer history through film and documentaries. Even though there was no singular person we learned about that matched my identities exactly, just learning about queer existence was enough to propel me to seek out more. I was delighted to find instances of queer Mexican people and communities especially, their sheer existence a radical act of resistance against our staunchly traditionalist culture. Finding representation and validation in gender nonconforming behavior throughout Mexican indigenous cultures, like in the Zapotec culture of Oaxaca where the muxe reside was life changing. The more I widened my understanding beyond the American and colonized paradigms I was taught and the more I was able to connect to my culture, and ultimately with myself.

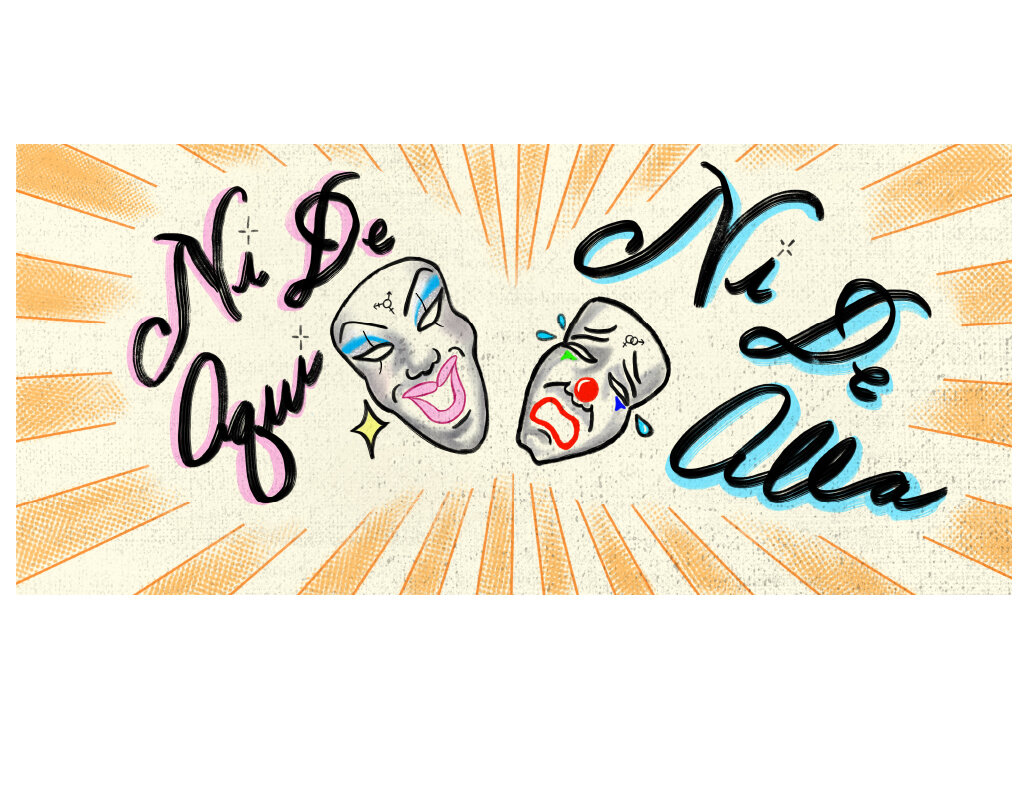

I’m queer, nonbinary and Xicanx, identities that exist in liminal spaces, in the in-between, ni de aqui, ni de alla. I’ve spent so long reciting the ways these identities cancel each other out, that I thought someone like me was not allowed to exist. I thought the combination of these identities would make all of them invalid, leaving me with nothing. I thought I was an oxymoron, a negative zero, my string of identities shining like fake pearls around my neck, betraying my secret to the world before I had a chance to figure out who I was. Now I wear them with a newfound pride forged with the help of community, advocacy and intersectionality. I still don’t know exactly where I fit, but now I know that I can make room.

I’ve always felt different. But now, I no longer feel wrong.

L.V. Loya Soto is a writer, multimedia journalist, and artist from California. they are a magazine and opinion writer, with a passion for the radial impact of immersive storytelling.